- Home

- “Worse than Chernobyl”: Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site and Its Legacy

21 March 2024

“Worse than Chernobyl”: Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site and Its Legacy

As Russian President Vladimir Putin continues threatening the West with the possibility of nuclear war after revoking Russia’s ratification of the 1996 global treaty banning nuclear weapons tests, Kazakhstanis living close to the former nuclear test site say, “Let our suffering be a lesson to others.”

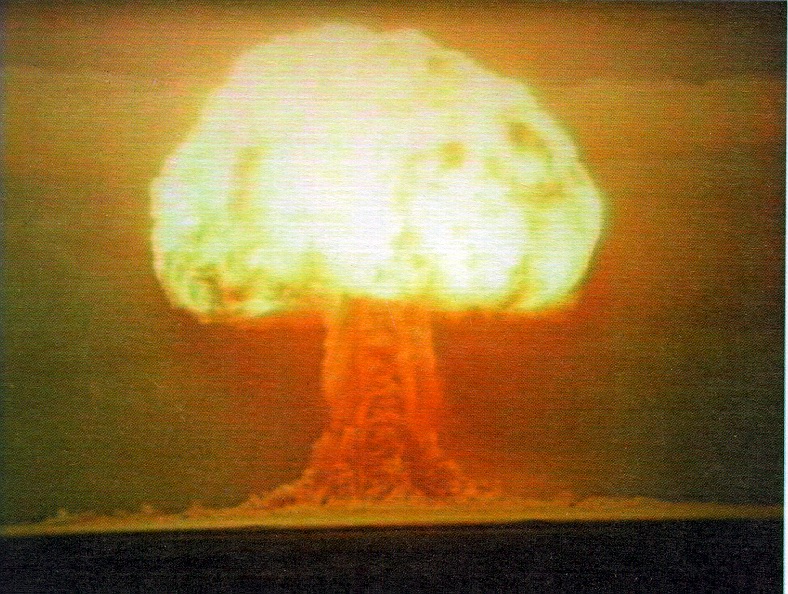

Photo taken of a nuclear test at Semipalatinsk Test Site. Image: gov.kz

When the United States dropped the first nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, it was a tragic event that changed the course of the world’s history. However, for the Soviet Union, it was a sign that they needed to create their own. Four years later, on 19 August 1949, the Soviets held their first atomic bomb testing.

It was the first of 456 nuclear bombs that would be tested for the next forty years at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, also known as the Polygon. Semipalatinsk, today called Semey, a city 75 miles from the testing site, “held a sacred meaning to Kazakhs,” writes Togzhan Kassenova, a nonresident fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment. Besides the “steppe, hills, low-range mountains, pine forests, and the Irtysh River,” it was here that in 1917, the Kazakh intelligentsia established the Alash Orda political party, which aimed to gain independence from Russia. Despite the executions of the party’s leaders in the 1930s, the present Kazakh population speaks highly of Alash Orda and its members, as they represent the anticolonial movement in the history of Kazakhstan.

Yet, for the Soviet government, the steppe was a perfect testing site during the Cold War race with the United States. “Locals heard a roar, followed by the earth shaking, the walls of clay houses breaking, and windows shattering, as a nuclear mushroom shape filled the skies,” Kassenova illustrates the locals’ memories of the first nuclear test. “A radioactive cloud blanketed the nearby settlements within hours before drifting far from the epicentre.”

“It was a nuclear disaster four times worse than Chernobyl in terms of the number of cases of acute radiation sickness,” NewScientist reports, adding that in the 1950s and early 1960s, there were more nuclear bomb tests than anywhere else in the world. Yet the health consequences and potential danger of living close to the nuclear test site were not revealed to the public. For years, the local population continued to be misinformed about the threat of radiological activity in close proximity.

Nevada-Semipalatinsk Movement

The testing went on for forty years, further damaging the population’s lives and health, until in 1989, the anti-nuclear movement “Nevada-Semipalatinsk” was formed in Kazakhstan. One of the movement's leading voices was Kazakh author, poet, and Soviet dissident Olzhas Suleimenov.

“I said that we will call this movement not ‘Semipalatinsk,’ but ‘Nevada-Semipalatinsk,’ because these two super polygons are like Siamese twins: if one gets sick, then so will the second, if one stops, then the other will shut up,” Suleimenov said in his interview with Vlast.kz. “Therefore, we decided: let’s stop our test site, then the Americans will stop theirs. That was the task, and it turned out to be doable.”

A 1989 march by the Nevada-Semipalatinsk anti-nuclear movement. Image: gov.kz

The possibility of any sort of movement’s existence in the Soviet Union was due to the “brief moment of democracy,” as Suleimenov called the period under the last Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev. Once established, the movement was unstoppable. After two years of its existence, the “Nevada-Semipalatinsk” movement was able to close the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site.

On 29 August 1991, on the 42nd anniversary of the first nuclear test, Kazakhstan’s first President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, closed the test site—however, consequences followed for years to come.

Remaining Consequences of Nuclear Testing

Due to the strong grip of the Soviet government on censorship, many of the horrifying consequences of the testing weren’t known to the public until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. However, according to NewScientist, despite many reports being destroyed, a few escaped Soviet censorship. One such report of the expeditions in 1956 and 1957 revealed “considerable radioactive contamination of soils, vegetable cover, and food” in eastern Kazakhstan.

Boris Gusev, a chief scientist at the Institute of Radiation Medicine and Ecology in Kazakhstan, says that one report recorded 638 “hospitalized with radiation poisoning” people in the city after the 1956 test, which was “more than four times the 134 radiation cases diagnosed after the Chernobyl accident.” The number of dead is unknown.

When Kazakhstan closed the test site, there was still a long road ahead in dealing with the outcomes of over forty years of nuclear tests. Together with the U.S. and Russia, Kazakhstan was able to rehabilitate the territory, transfer nuclear weapons to Russia, and get rid of the “loose nuclear material that was vulnerable to potential smugglers,” as former President Barack Obama said during a trilateral meeting with former President Nazarbayev and former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev in 2012.

Crater from a USSR nuclear test at Semipalatinsk. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Despite the successful completion of the collaboration between the three countries, “the Semipalatinsk story is not quite finished,” RFE/RL quotes Leon Ratz, senior program officer at the Washington-based Nuclear Threat Initiative. In his analysis, “As long as the nuclear materials remain buried in those tunnels, the security, proliferation, and environmental risks will have to be managed. Kazakhstan will need to maintain effective security around this vast site with a well-trained, well-equipped response force. Environmental impacts will have to be continuously assessed.”

There is a lot of evidence to support his words. Among “the legacy of Soviet nuclear tests,” Kassenova mentions high cancer rates and early death, as well as “miscarriages, complicated pregnancies, and stillbirths.” In 2012, photographer Phil Hatcher-Moore documented those who live in the area and showed babies who, even decades after closing the test site, were born with complications. The residents of the area adjacent to the former Polygon share their frustration over the lack of help from the government with rehabilitation and their health.