- Home

- Journalists Faced with Social Media Abuse Following Shusha Global Media Forum

4 August 2023

Journalists Faced with Social Media Abuse Following Shusha Global Media Forum

Last month, international journalists and media experts attended the Shusha Global Media Forum, and while the discussion was varied and balanced, many pro-Armenian lobbyists are outraged and harassing those involved.

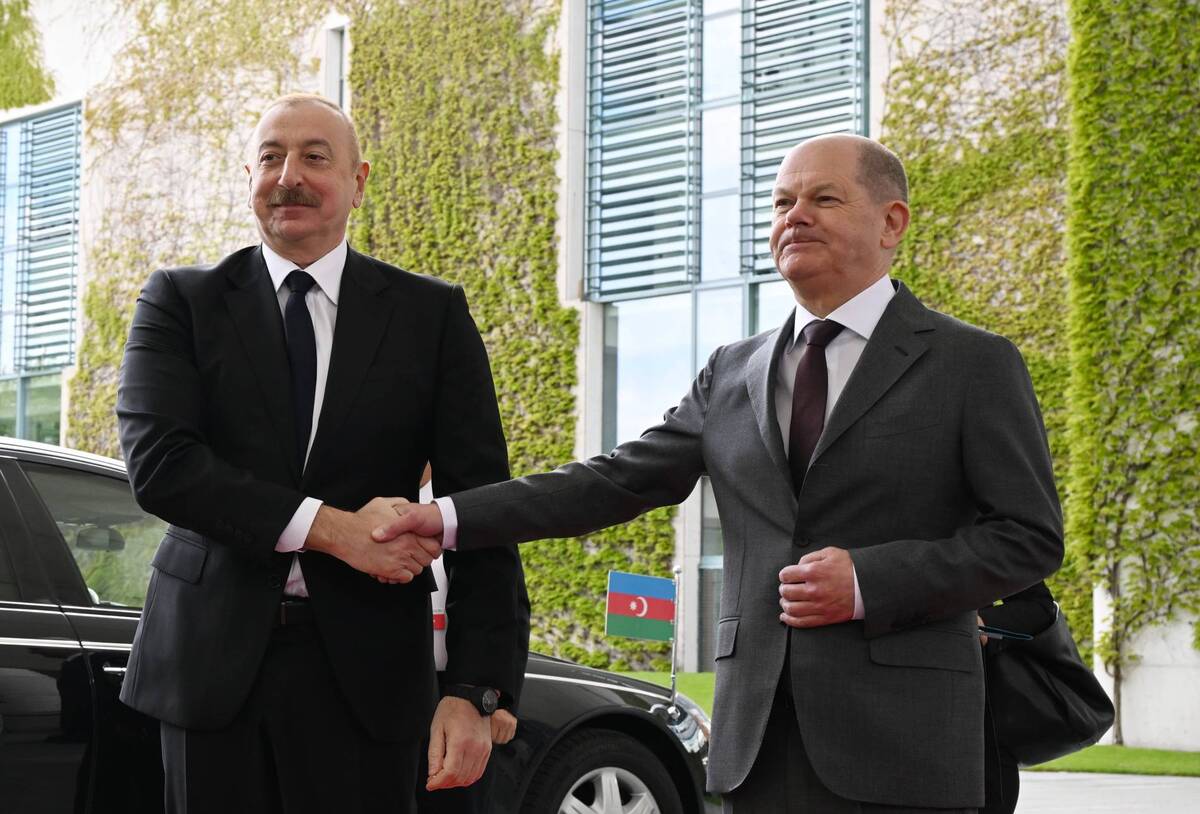

Image: president.az

Last month, the Shusha Global Media Forum, “New Media in the Era of the 4th Industrial Revolution,” was attended by international journalists and media experts in the liberated city of Shusha in Azerbaijan's Karabakh region. As discussed in a previous article by The Caspian Post, the topics of discussion at the forum varied, ranging from the potential role of AI in journalism to media management strategies to ensuring the safety of journalists. This last topic is particularly important, considering the outpouring of vitriol that the forum’s participants have since experienced on social media.

A Twitter activist and a pro-Armenian commentator Lindsay Snell is at the forefront of the attacks, going as far as to tweet the names of the foreign journalists and media experts that attended the forum, a move which can be interpreted as inviting others to contact, or even harass, the attendees. She further commented that attending the forum was “unethical” considering Azerbaijan’s “ongoing blockade is starving 120,000.” This allegation is a common occurrence on social media to justify the uproar surrounding the forum. However, as stated in an article by The Caspian Post, the humanitarian crisis in Karabakh is more complicated than pro-Armenian lobbyists are alleging, with Armenians themselves blocking the alternative route to the closed Lachin Road.

One group of attending journalists whose names were released by Snell represented TRT World (an English-language Turkish public broadcaster), and they unfortunately have experienced especially harsh backlash on social media. Jaffair Hasnain, Maria Ramos, and Oubai Shahbandar all received multiple replies to their tweets about the event making allegations about their characters, incentives, and motives, as well as hurling profanities and insults. Even more egregiously, Ramos stated in an interview with caliber.az, that some of the online abuse directed towards her was of a sexual nature.

Additionally, the Media Development Agency of the Republic of Azerbaijan issued a statement pointing out that the purpose of the forum was “to discuss the future directions of development in journalism” and that, unfortunately, this important event is being redirected and “politicized” by pro-Armenian lobbyists. The statement also argued that the slander and hatred being levied against the attending journalists is “in no way compatible with journalistic ethics.” This point was reiterated by Zaur Mammadov, a political scientist, who replied to Snell stating that using the forum as “a tool for hate speech” is unacceptable. Ayshan Aslan-Mammadli, a lecturer at Baku State University, agreed, stating that those involved in the abuse are “biased towards the rights of influential media representatives.”

Indeed, the social media abuse seems to be motivated by a desire to intimidate and harass any journalist who attended this event in an effort to dissuade them from visiting Azerbaijan. This not only attempts to prevent Azerbaijan from having the opportunity to tell its story to the international media but also infringes upon the freedom of the press to choose where and on what it reports.

Another common theme of the online abuse surrounds allegations of a financial incentive for the journalists to attend the forum. Journalist and researcher Anastasia Lavrina tweeted a photo of herself and two attendes and received a GIF of money being thrown in response. Lavrina’s tweet featured Richardas Lapaitis, a Lithuanian journalist who witnessed first-hand and wrote about the 1992 Khojaly massacre. His reasons for travelling to Karabakh at such a dangerous time, he states, were due to the death of his friend’s brother during Black January and the “injustice in the fact that Azerbaijan was under an information blockade, while many foreign journalists worked in Armenia,” and not, as has now been suggested, financial gain.

As Lapaitis points out, foreign journalists have long been present in Armenia. Yet, they do not appear to have received the same amount of backlash and abuse as those visiting Azerbaijan receive. For example, in March 2017, the International Bloggers Forum was held in Khankendi/Stepanakert and attended by bloggers from 11 countries, and in February 2018, foreign journalists from Russia, Latvia, Hungary, France, Algeria, and Italy visited Karabakh and met with high ranking members of the Armenian clergy and politicians—both of these international media events occurred while Karabakh was under Armenian occupation. However, unlike the current situation, pro-Armenian tweets about these events do not contain any replies of abuse, hate speech, or bullying from Azerbaijanis or supporters of Azerbaijan.