- Home

- Gardabani’s Ashiqs: Guardians of an Ancient Musical Tradition

Gardabani’s Ashiqs: Guardians of an Ancient Musical Tradition

Onnik James Krikorian heads to Gardabani to meet leading surviving exponents of the Turkic troubadour tradition in eastern Georgia’s Azerbaijani community. Despite many challenges for exponents, the art form continues to inspire a passionate following.

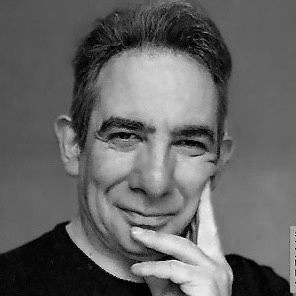

Perviz Mirzeyev / Image: Onnik James Krikorian

Nestled within the lush green landscapes of Georgia’s Kvemo Kartli region, the municipality of Gardabani is home to many from the country’s largest ethnic minority: Azerbaijanis. Here, despite concerns of dwindling numbers, the age-old Turkic tradition of wandering minstrels has continued. Known as ashiqs, these troubadours are skilled in the art of performing poetry over music, usually performed on the saz, a stringed instrument resembling a long-necked lute.

Their art has been an integral part of Azerbaijani culture for centuries. Indeed, in 2009, it was inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO. In Kvemo Kartli, where most of Georgia’s approximately 233,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis reside, the Ashiq tradition helps promote the community’s rich cultural heritage.

“I believe that it is through the saz and ashiqs that we have preserved our language, heritage, religion, and identity in this country,” said Georgian-Azerbaijani Ashiq Nargile, one of a few surviving practitioners of the art form in the country, in an interview. “Georgians can’t live without music: they are always singing and dancing. […] For Azeri-Turks in Georgia, our music is also very important to us. Especially the ashiq tradition.”

An ethnomusicologist once shared with me the insight that the minstrel or bard tradition, now closely associated with Azerbaijani music, was once a pan-Caucasian musical tradition. However, in Georgia’s Kvemo Kartli, the various schools of Ashiq music have their own unique style. For instance, Borchali Ashiq music is considered more melancholic than its more light-hearted and entertaining counterpart in Azerbaijan.

But despite these distinctions, the core essence of Ashiq music lies in its ability to be a potent medium for storytelling, preserving national and community history through songs and poetry.

Sitting in the yard of Perviz Mirzeyev, the son of the late Gardabani Ashiq Aslan, I have the privilege of conversing with 88-year-old Zahid Ələmpaşalı, a charismatic local poet. He passionately emphasizes the importance of this ancient art. “It should not be forgotten,” he tells me. “There are poets in Baku, but people don’t hear their [message]. But the words of the ashiqs are easy to remember because they reach the hearts.”

Ələmpaşalı recited one poem at the funeral of Ashiq Aslan in 2014.

The end of my journey draws near,

Bless those who witness with knowing fear,

Breath comes in gasps, the pillow like stone,

Bless those who come, so I’m not alone.

When the moon descends, it fades away

Breath is retracted from the lifeless clay.

I am departing from this earthly fray.

Best wishes to those who choose to stay.

Sorrowful, I seek a helping hand,

Grant Zahid forgiveness, it is my demand.

Thanks to those who remember me,

Sending blessings time after time.

However, Mirzeyev shares his concern that the tradition is slowly fading away as fewer young people take up the arduous path of becoming an Ashiq. To achieve this esteemed title, an Ashiq is required to master around 75 songs, commit to memory the words of the master Ashiqs who came before them, and possess knowledge of numerous folk tales—a daunting journey.

“For example, take myself,” Mirzeyev confesses, “Today, I do not continue this art, and my brothers have also chosen different professions. There is no promotion of the ashiq tradition. However, my father devoted his life to ashiq music and saz. He was awarded medals by the Georgian state for his dedication.”

Ashiq Aslan Kosalı, born in 1929 in the same village, embarked on his Ashiq journey in 1959. In a touching tribute to his father and the Ashiq tradition more generally, a small museum has been established in one room of Mirzeyev’s house, housing memorabilia that reflects the life and legacy of this legendary figure. Outside, a new building is nearing completion to rehouse a collection of items related to the tradition.

I talk to Sakhib Mustafayev, a local teacher who recognizes the importance of exposing young minds to this cultural treasure. He already takes pupils to the museum to acquaint them with the art, hoping to ignite a spark of interest and passion for the ancient tradition.

Ashiq Aslan Kosalı was not just a local luminary; he represented ashiq musical culture internationally, participating in festivals in Iran, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Azerbaijan. “I’m proud of my father,” beams Mirzeyev, “Wherever I go—Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan—I am known as the son of Ashiq Aslan Kosalı, keeping his legacy alive.”

In a rapidly changing world, where traditions sometimes struggle to find their place, the Gardabani Ashiqs stand tall, weaving their melodies through time, preserving the history of their community, and leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Georgia. Though still a daunting task, Mirzeyev hopes the Georgian Ministry of Culture will grant official recognition to his house museum.

As long as there are those like Zahid Ələmpaşalı and Perviz Mirzeyev who are determined to keep the flame of Ashiq tradition burning, these soulful melodies will continue to resonate in the hearts of those who hear them.

Read this next