- Home

- Decolonialism in Kazakhstan: Why Now?

8 December 2023

Decolonialism in Kazakhstan: Why Now?

Kazakhstan has been an independent state for almost 32 years. However, never before were its citizens so focused on their own history, traditions, and language. Now, with the rising popularity of the academic term “decolonialism” in the country’s everyday life, Kazakhstan is going through its own metamorphosis.

Image: Colobus/Shutterstock

A few years ago, “decolonialism” was a term used by academics on a professional level when reflecting on the history of Kazakhstan. Today, if you Google “Decolonialism in Kazakhstan” in Russian, you will see countless articles from Forbes Kazakhstan to BBC Russian Services. Evidently, it has become a widely-talked-about topic not only among the academics. Today, the younger generation is braver in stating what their parents would avoid acknowledging and even discussing. That is—Russians colonized us. More than that, the youth’s rising political awareness points out that Kazakhstan is still under the influence of its former oppressor.

Kazakhstan is a young country, getting its independence in 1991—as a matter of fact, it was the last country to leave the USSR—it is going to celebrate its 32nd anniversary on 16 December this year. Prior to being part of the Soviet Union for 71 years, Kazakhstan was a colony of the Russian Empire since the 18th century. A fact that many Russian politicians on Kremlin-propaganda channels never forget to mention. It was as if, by not having their sovereignty, Kazakh steppes with nomadic tribes didn’t exist until Russia discovered and colonized them.

Nonetheless, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, for almost 32 years, Kazakhstanis were able to govern themselves and have their own official language, Kazakh; their own anthem, which for years was a national song sung by common folks; and the ability to learn their own history, which was not taught in the Soviet times. Yet, why did Kazakhstanis suddenly become so obsessed with the concept of decolonialism this year? Hasn’t it already been done? Haven’t they overcome the downfalls of colonialism the moment they became independent?

The beginning of war in Ukraine in 2022 made Kazakhstanis realize the possible dangers of being neighbours with your former colonizer. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has demonstrated that not only are they not ashamed or apologetic for their colonialist past, like their Western counterparts, for example, but they even dream of expanding the borders of the Russian Federation and annexing all its former colonies.

The Russian influence is also more tangible, as despite becoming a sovereign republic, Kazakhstan remains mostly Russian speaking. Precisely, Kazakh is the only state language, but Russian is the official language of communication along with the Kazakh language. This can be explained by the government’s focus on preserving its Russian-speaking part of the population and not letting them feel discriminated against. Due to the diverse demographic of its population, when the country gained its independence, there were less than 40 percent of ethnic Kazakhs in Kazakhstan. The other 60 percent were ethnic minorities, the biggest one being Russians. Today, more and more citizens realize with horror that they know Russian and English better than Kazakh while living their whole lives in Kazakhstan.

On top of that, the Russian language’s dominance in Kazakhstan was further enforced through entertainment—from TV shows to books and magazines, it was easier to get information in Russian than in Kazakh. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the feeling of belonging to Russia culturally has never gone away. And why would it? Kazakhstan was always proud of its multiethnic demographic and never had any religious or ethnic conflicts—celebrating both Muslim Ramadan and Orthodox Christmas, for example. An idyllic utopia. Or so it seemed.

The other side of the coin, often overlooked by officials, was that some ethnic Kazakhs, usually from smaller towns or villages, would find it oppressive having to speak Russian in ‘their own country,’ giving way to rising nationalism often masquerading under the pretense of return to traditionalism. There were instances where if a conflict would happen between an ethnic Kazakh and an ethnic minority person, one could be told ‘to go back to their country.’ However, in recent years ethnic tensions have started becoming not the result of an argument escalating but rather the goal in itself. So-called language patrols were going around harassing Russian-speaking cashiers, servers, and even doctors. The ‘language patrollers’ were filming these harassments and then uploading them online. Coincidentally, it was always ethnic Kazakhs verbally attacking ethnic Russians for their lack of knowledge of the state language. That didn’t last long. Soon, the Kazakh government put an end to this ‘trend’ by persecuting those responsible for these acts, which, according to Article 174 of the Kazakh Criminal Code, “Inciting social, national, tribal, racial, class, or religious hatred” can result in two to seven years in prison.

Yet, with the beginning of the war in Ukraine, these language patrols weren’t needed anymore, as the mindset of Kazakhstanis toward different ethnic backgrounds has shifted. Seeing their former colonizer try to invade the territory of another post-Soviet sovereign state made Kazakhstanis feel eerie. Are we next? Does imperialism have limits when it sees no boundaries? Did the former colonizer get us fooled by pretending to be our friend all these years? These and many other questions are not that unsubstantiated when Russian politicians openly say that Kazakhstan is next and it’s Northern territories, in fact, belong to Russia.

Russian imperialism was able to do in a year what Kazakh nationalists couldn’t do in 30 years—make people want to learn and speak Kazakh. In October 2023, it was announced that the new draft law on the media plans to increase the Kazakh language in media from 50 to 70 percent. Culture Minister Aida Balayeva informed the press that the transition will begin in 2025 with a five percent increase per year.

This draft law is not surprising, considering that citizens have already started showing more interest in the state language. There is a rising number of songs in the Kazakh language, and Kazakhstani media that used to have only Russian-language websites are now releasing their Kazakh versions. Even common people started taking classes in Kazakh to better their knowledge. One such example is a feminist activist, Veronica Fonova, whom I interviewed earlier this year, who has been actively learning Kazakh and practicing it on her TikTok. The video of Veronica speaking Kazakh and sharing her efforts with her followers gained over 200,000 views and many positive and supportive comments from fellow citizens.

For years under Soviet rule, Kazakhs (and other minorities) had to denounce their own culture and language to whitewash themselves to seem civilized enough for the colonialists. The act was so common for minorities and people of colour in the USSR that Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov coined the term mankurt in his novel The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years, for slaves who were brainwashed by their oppressors and had lost touch with their ethnic homeland. Mankurt became a common term for many minorities, symbolizing the Russified (colonized) state of mind, the disapproval of everything traditional, and the lack of knowledge of one’s own history.

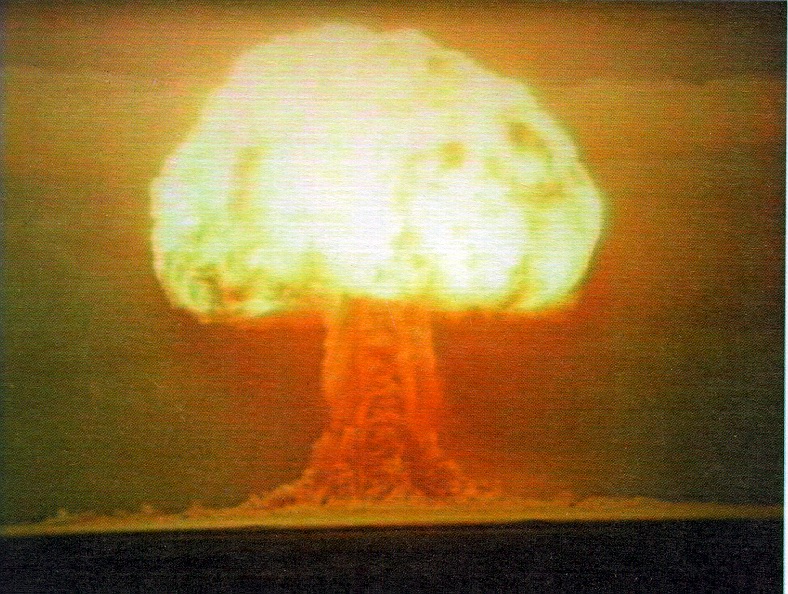

Decolonialism is not only about the language, but it is also the main focal point in Kazakhstan. Besides the language, historical facts are finally being acknowledged more openly and boldly. 31 May is now the Day of Commemoration of the Victims of Political Repressions. Among them are the Kazakh Famine of 1930-1933, also known as Asharshylyq in Kazakh, which is the equivalent of Ukrainian Holodomor; nuclear tests in Semipalatinks; and the horrendous killings of the Kazakh intelligentsia in the 1930s. With this awareness comes the driving force toward self-realization and the acknowledgment of one’s roots and history, even if it costs upsetting the former colonizer. The truth may hurt, but it is ignorance that steals any chance for a better future. Although language is just the tip of the iceberg, the determination to weaken the Russian language and with it the tight grip of the former empire only further enforces and confirms the efforts of the Central Asian country not to let history repeat itself.

Read this next